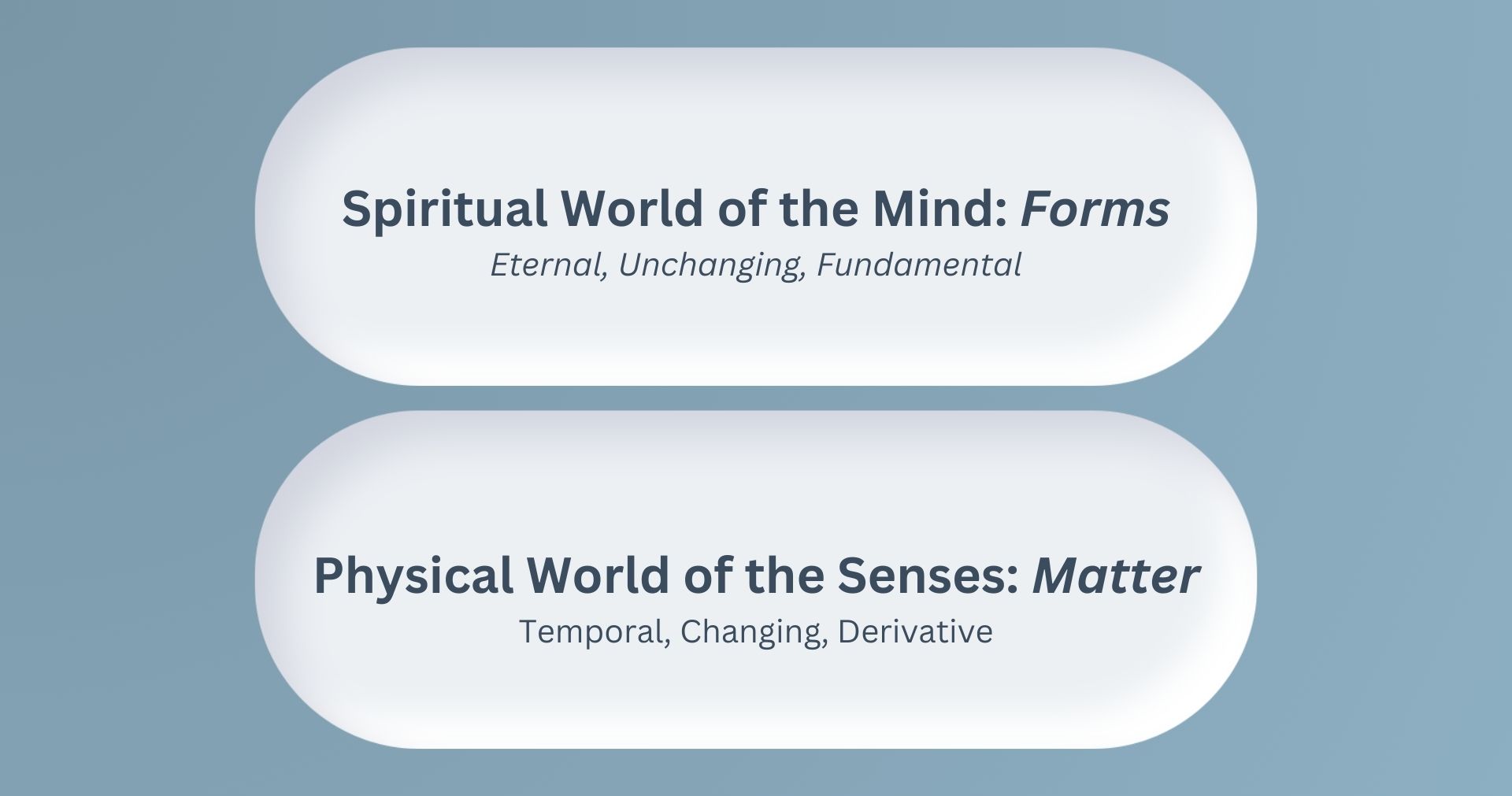

Plato famously creates “two worlds”: the world perceived by the senses and the world perceived by the mind. The world of the senses is impermanent and shifting (more on that later), while the world of reason is eternal and unchanging. Individual things may become more or less beautiful, but beauty itself never changes. Individual dogs may come and go out of existence, but what it is to be a dog never changes. These two worlds are, of course, only two different aspects of the same world—there is only one world. But the spiritual realm is more fundamental and real than the physical. The one is eternal and unchanging, while the other is transitory and quickly shifts. The physical realm derives its being and reality from the spiritual. If beauty didn’t exist, nothing could be beautiful. If there were no such thing as what it is to be a human being, then no human beings would exist. Even the colors and shapes that are basic to physical objects have a nature or essence that makes them what they are. There are such things as redness and being square.

This view explains what is otherwise a very puzzling feature of our language. We have nouns that are names for individual things like “Bob Dylan” or “the Empire State Building,” but we also use nouns for things that are not individual, but are common to multiple individuals, such as “house,” “dog,” “red,” and “beauty.” The name “Bob Dylan” refer to only one object. But “house” is quite different. There are many houses, each of which is equally a house. There’s only one thing that is truly Bob Dylan. So why do we call multiple things by the same name? The most natural explanation is that there is something in common to all those things, by virtue of whose presence we apply the same name. There is something shared by all houses by virtue of which we call them a house. This shared thing, Plato says, is a “form” (eidosor idea, sometimes translated “Form” or “Idea”) or “essence” (ousia). The form or essence is what the thing really is.

We cannot explain the world around us without including these forms or essences. They make things what they are, even more than the material out of which they are composed. They tell us what kind of thing something is—where it fits into the overall scheme of the world. It’s not just “that thing”; it’s “a book.” Yes, it is a concrete, specific thing, but its essence tells us what kind of thing it is—where it fits in our taxonomy of being. Things would not be what they are without the presence of these essences. And individual things become what they are through participation in these nonphysical essences.

The relationship between these two worlds is one of dependence—the material depends on the spiritual—though Plato famously waffles on the precise language we should use to express this relationship. He generally calls it “participation”; the physical and temporal participates in the spiritual and eternal. The spiritual and eternal comes to bepresent in the physical as things change over time. So a pile of lumber, when acted upon by an agent with the knowledge to bring about the change, can be transformed into a house. “House” comes to be present in the wood through the activity of the homebuilder. What a house is imposes limits and constraints on how the builder can build it. A house can only come into being if it fits in with what it is to be a house, something that is eternal and unchanging. The spiritual structures the physical, and the physical is what it is only through its incomplete though genuine participation in the more than physical realm.

The spiritual world is the rational world. The nymphs and centaurs of Greek mythology were spiritual beings present in the Greek imagination. Plato, like philosophers before him, rejects these mythological entities in favor of rational, organizing structures. Without the spiritual and rational, the physical world would be disorganized chaos, with no structure whatsoever. In his dialogue Gorgias, he says it would be a “world-disorder,” rather than a “world-order.”[1]

Christians can appreciate this insistence upon the spiritual, while still recognizing that Plato’s view is ultimately unsatisfying. That there is a pervasive spiritual aspect to creation, present everywhere, is certainly true, but because Plato does not have an adequate theology, the complete nature of the spiritual world is unknown to him.[2] Compared with materialism, this view is attractive. But it is a long way from a recognition of the true Creator.

In Christianity, there is room for both angels and natural laws, but always derived from the sovereign hand of their Creator. At creation, God made everything out of nothing, by the word of his power. Creation is the manifestation of the glory of God’s eternal power, wisdom, and goodness. That it is structured rationally and orderly is implied by its being caused by wisdom. Platonism, in its insistence on the reality and fundamentality of the nonphysical, concurs with this part of Christian truth. There is an orderly, rational world, which consists of more than the material and which is ultimately comprehensible only when we see the eternal, yet imminent, source of that order.

Later philosophers will question whether Platonic forms are the only way to explain the rational structure of the universe. Aristotle, for example, agrees that there are forms, but he disagrees that they exist in a separate realm or world. For Aristotle, the forms are real and nonphysical, but are only immanent in physical things. There is an essence of beauty, but that essence only exists in beautiful things—it does not and cannot exist anywhere else.[3]Aristotle also draws a distinction between essential forms, which tell us what kind of thing something is, and accidental forms, which tell us an attribute of a thing, but not what kind of thing it is.[4] So “red” and “book” are both forms, but they are not quite the same kind of forms. If something is a book, we know what category of being it falls into, since being a book tells us about its essential nature. But if something is red, we don’t yet know its essence. There are red books, red cups, and red dresses. Each of those is a different kind of thing, though each is red. Furthermore, there are not only individual things and forms, but also different kinds of forms: essential ones (which are necessary to the object and are what the object is) and accidental forms (which are not part of the object’s nature but are still truly present in the object). Plato himself seems to be moving toward this distinction in his later dialogues.[5]

David Talcott’s publications have appeared in numerous outlets including Public Discourse, Eikon: A Journal of Biblical Anthropology, Human Life Review, and First Thingsonline.

David Talcott (PhD, Indiana University) is fellow of philosophy and the graduate dean at New Saint Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho. He is a program manager for truthXchange and a ruling elder in the Presbyterian Church of America.

[1] Gorgias 508a. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations of Plato in this book are taken from The Complete Works of Plato, ed. John M. Cooper (Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, 1997).

[2] See chapter 8 for additional discussion of Plato’s theology.

[3] See Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, I.6, for one example of this argument, which is present in a number of places in Aristotle.

[4] See Aristotle, Metaphysics, Book VII, for one place where he discusses this distinction. Aristotle’s discussions of these issues are notoriously dense and difficult.

[5] See, for example, Sophist226b–231d.

Comments